During the summer of 2023, officials in the Monroe-Woodbury High School decided to crack down on student lateness for the 2023-2024 school year. They have turned to technology to help enforce an existing policy that states that a student will receive detention for every three times that they are late to school.

While the rule is technically not new to the Code of Conduct– according to Monroe-Woodbury High School Principal of the last two years, Ms. Soto– this is the first year in which systems are being used to enforce this policy and hold students accountable.

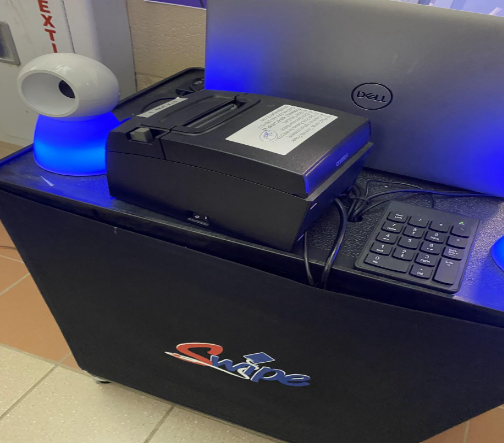

To keep track of this, students who are late to school are required to scan into the building using their student IDs and receive generated passes that keep track of the number of lates that the student currently has on the bottom of the paper. When a student reaches a lateness that is a multiple of three, an extra pass is printed that states that the student has detention. From there, they are instructed by one of the attendance officers to report to the Dean of Students, Mr. Ferrier.

Even though some students associate a negative connotation with penalization, officials make it a point to assure students that these actions are taken in their favor.

“I’m more concerned about the lesson than the consequence,” said Mr. Ferrier. “It’s really, really important to practice [self accountability], now as a young person, regardless of if you’re a freshman or you’re a senior.”

While some administrators in the school focus on the positives of these disciplinary actions, some students, like Alyssa Williams, a current senior at Monroe-Woodbury high school, don’t necessarily see these benefits.

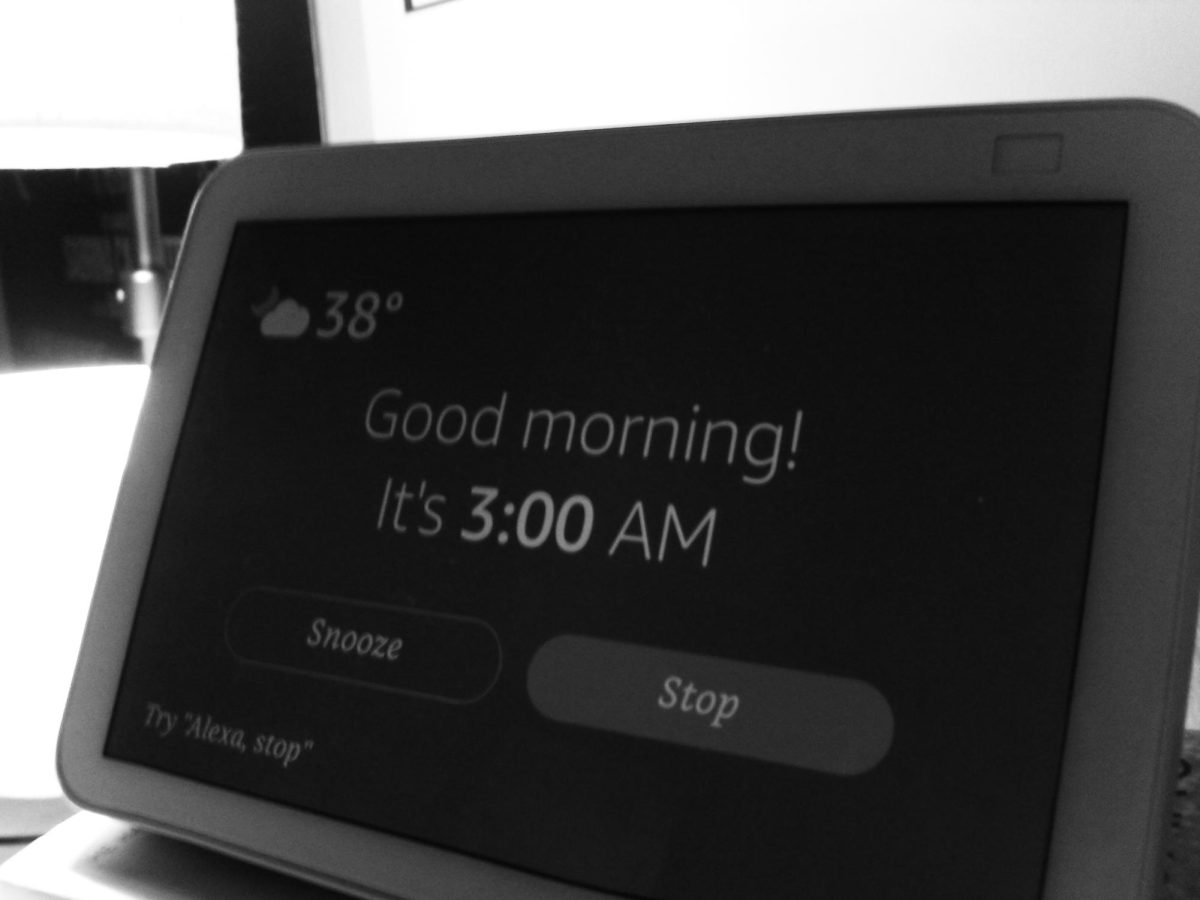

“I feel like it’s not necessary because every morning is not going to be the same,” said Williams. “Some mornings are tougher [to get to school on time] than other mornings”.

In response to such feedback, Mr. Ferrier spoke on the importance he places on understanding a student’s circumstances when deciding punishments.

While the dean does have to report to Ms. Soto, he is allowed a level of authority in assessing the situation and assigning an appropriate result. This is where he uses the opportunity to understand the predicaments that might make a student late.

“Somebody had to drive somebody to the airport that morning, somebody’s dealing with an illness in their house, somebody has to help get their younger brother on one of the elementary buses,” said Mr. Ferrier, explaining the variables that contribute to accidental lateness, “It’s not just one size fits all.”

It is Mr. Ferrier’s hope that developing a more human-based approach to this rule will encourage students to feel comfortable with expressing their situations to officials in the high school, while simultaneously teaching them the importance of showing up on time.

The dean of students and the high school’s principal shared ideas that these rules help prepare students for the near future in college, and for the real world in their careers. They also express that in addition to these points, rules like the three-latenesses-equals-detention rule help promote the values of punctuality.

“When you show up late to some place that means you have no regard for that person,” said Ms. Soto. “Maybe that’s not the intention, but it’s definitely how it’s perceived.”

Some teachers also agree with this idea, like Ms. Rickard– who has been an English teacher in the high school for the past 10 years.

“Punctuality shows people you care about their time,” said Ms. Rickard.

Additionally, it is agreed by some adults in the high school that the placement of this rule, and other rules alike, typically boil down to a blatant topic: student safety.

“We’re in a culture where people are afraid that bad things can happen in schools, and so they want to make sure– even more so now than ever– that every student is accounted for, and where they need to be,” said Ms. Rickard. “If you know you can be on time, you should always be on time.”